What is infection?

The invasion and multiplication of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites that are not normally present within the body. An infection may cause no symptoms and be subclinical, or it may cause symptoms and be clinically apparent.

An infection may remain localized, or it may spread through the blood or lymphatic vessels to become systemic (body wide). Microorganisms that live naturally in the body are not considered infections. For example, bacteria that normally live within the mouth and intestine are not infections.

Reference: Medical Definition of Infection, Medical Author: William C. Shiel Jr., MD, FACP, FACR; https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=12923

How Virus and Bacterial are different from each other?

This is important to understand, because bacterial and viral infections must be treated differently. Misusing antibiotics to treat viral infections contributes to the problem of antibiotic resistance.

Bacteria and viruses are too tiny to be seen by the naked eye, can cause similar symptoms and are often spread in the same way, but that’s where the similarities end.

Microorganisms capable of causing disease—pathogens—usually enter our bodies through the mouth, eyes, nose, or urogenital openings, or through wounds or bites that breach the skin barrier.

A bacterium is a single, but complex, cell. It can survive on its own, inside or outside the body. Unlike bacteria, they need a host such as a human or animal to multiply. Viruses cause infections by entering and multiplying inside the host’s healthy cells.

Reference: Differences between bacterial and viral infection, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/bacterial-vs-viral-infection

Can you elaborate more about virus?

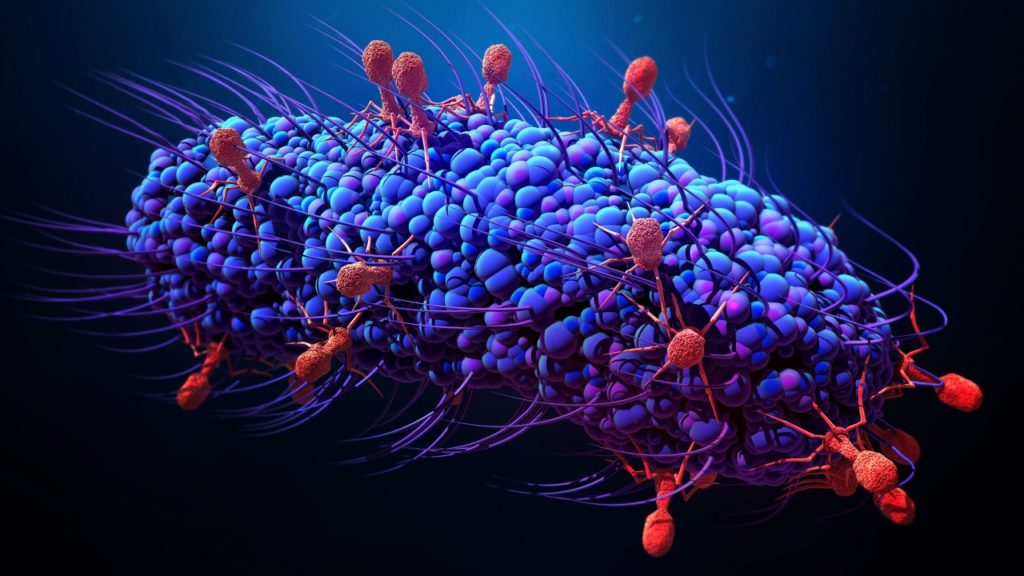

Viruses are tiny, ranging in size from about 20 to 400 nanometers in diameter (see page 9). Billions can fit on the head of a pin. Some are rod shaped; others are round and 20 sided; and yet others have fanciful forms, with multisided “heads” and cylindrical “tails.”

Viruses are simply packets of nucleic acid, either DNA or RNA, surrounded by a protein shell and sometimes fatty materials called lipids. Outside a living cell, a virus is a dormant particle, lacking the raw materials for reproduction. Only when it enters a host cell does it go into action, hijacking the cell’s metabolic machinery to produce copies of itself that may burst out of infected cells or simply bud off a cell membrane. This lack of self-sufficiency means that viruses cannot be cultured in artificial media for scientific research or vaccine development; they can be grown only in living cells, fertilized eggs, tissue cultures, or bacteria.

Reference: How Infection Works, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209710/

How are vaccine made?

Several basic strategies are used to make vaccines. The strengths and limitations of each approach are described here.

Weaken the virus

Using this strategy, viruses are weakened so they reproduce very poorly once inside the body. The vaccines for measles, mumps, German measles (rubella), rotavirus, oral polio (not used in the U.S.), chickenpox (varicella), and influenza (intranasal version) vaccines are made this way. The advantage of live, “weakened” vaccines is that one or two doses provide immunity that is usually life-long. The limitation of this approach is that these vaccines usually cannot be given to people with weakened immune systems (like people with cancer or AIDS).

Inactivate the virus

Using this strategy, viruses are completely inactivated (or killed) with a chemical. By killing the virus, it cannot possibly reproduce itself or cause disease. The inactivated polio, hepatitis A, influenza (shot), and rabies vaccines are made this way. Because the virus is still “seen” by the body, cells of the immune system that protect against disease are generated.

There are two benefits to this approach:

· The vaccine cannot cause even a mild form of the disease that it prevents

· The vaccine can be given to people with weakened immune systems

However, the limitation of this approach is that it typically requires several doses to achieve immunity.

Use part of the virus

Using this strategy, just one part of the virus is removed and used as a vaccine. The hepatitis B, one shingles vaccine and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are made this way. The vaccine is composed of a protein that resides on the surface of the virus. This strategy can be used when an immune response to one part of the virus (or bacteria) is responsible for protection against disease.

Reference:https://www.chop.edu/centers-programs/vaccine-education-center/making-vaccines/how-are-vaccines-made

Excellent beat ! I would like to apprentice while

you amend your website, how could i subscribe for a blog web site?

The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been a little

bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear concept

Great post. I used to be checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed!

Very useful info specifically the remaining section 🙂 I maintain such information much.

I used to be seeking this particular information for a long time.

Thanks and good luck.

I think this is among the most important info for me. And i am glad reading

your article. But wanna remark on some general things, The website style is perfect, the articles is really nice

: D. Good job, cheers